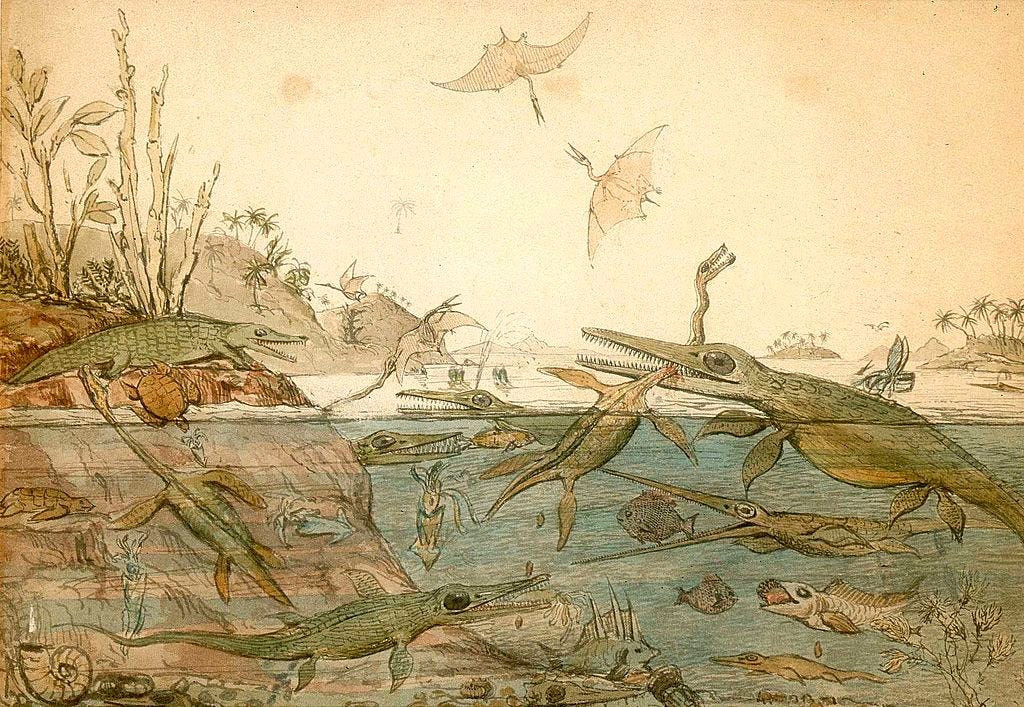

There rolls the deep where stood the tree

O Earth, what changes thou hast seen

-Tennyson, In Memoriam

As a person whose convoluted educational background- a story for another day- involved study in both the humanities and sciences, I often find my mind at the chaotic edge of those disciplines, where the domain of metaphor and myth mixes with that of the concrete description of the natural world. Since we humans perceive our little part of the universe through words, pictures and stories, these areas of thought are really not so far apart as we often think, and the words we use in our attempts to understand nature can have far-reaching consequences.

It is often said that the ancients, seeing dinosaur bones, thought them the relics of Dragons or Giants. People of a skeptical mindset enjoy a good scoff on behalf of our ancestors in this regard. And yet: Right on both counts, I say- they were the bones of dragons, a Dragon being after all a sort of mythic reptile, and Giant they surely were- some are now known to have been over 100 feet in length.

In fact, ancient philosophers were closer than us to the truth in one regard- they perceived the grand vastness of the cosmos with an appropriate sense of wonder and spiritual awe. To speak of Tyrannosaurus as cousin to a dragon does him far more justice than to consider him the great-great-grandfather of your chicken dinner. Modern people have developed a tendency, when speaking about nature and the universe, to want to shrink it down to a size we can understand. We want to visualize the solar system on a comprehensible scale- but in so doing, we lose the ability to see the reality of it- the horrifyingly vast distances of empty blackness between the planets, the tremendous speed of their rotation, the unimaginable extremes of heat and cold. We want to measure the vast stretches of time on a ruler. But in reducing the age of the earth to something easily graspable- whether that be the fundamentalist’s 6000 years, or the secularist’s color-coded timeline in a textbook, we lose sight of the immensity of what we are trying to describe.

Try for a moment to really imagine long periods of time. How far back does it actually make sense? A century? 500 years? A thousand? The oldest people I ever met were born perhaps 90 or so years before me- at the beginning of the 20th century. My grandmother knew people born in the 1870’s. Events might be remembered for a few hundred years- my maternal grandfather’s family had inherited a slightly confused account of their Russian German ancestry, based on an immigration event that took place in the mid 18th century. Interestingly, people living in ‘illiterate’ societies often have deeper memories than those who read- it was quite common across cultures for people to memorize minute details of family history back across several generations.

The world of even 400 years ago is mostly incomprehensible to average modern ‘Western’ people- a category which is rapidly growing beyond geographic borders thanks to the neocolonialism of advanced technology. Maybe we can vaguely comprehend a century, and perhaps the cultural changes of the last 200 years are not so great that we can’t ‘put ourselves in the shoes’ of people in the Age of Enlightenment, for example (although it is a stretch). But the further back we go, the more we lose the threads of direct connection, and thus enter into the world of story. Most people today would find it very difficult to understand the mindset of early British settlers in New England, whose world was inhabited by a menagerie of ghosts, spirits and witches and filled by the Almighty with divine meaning and mysterious purpose.

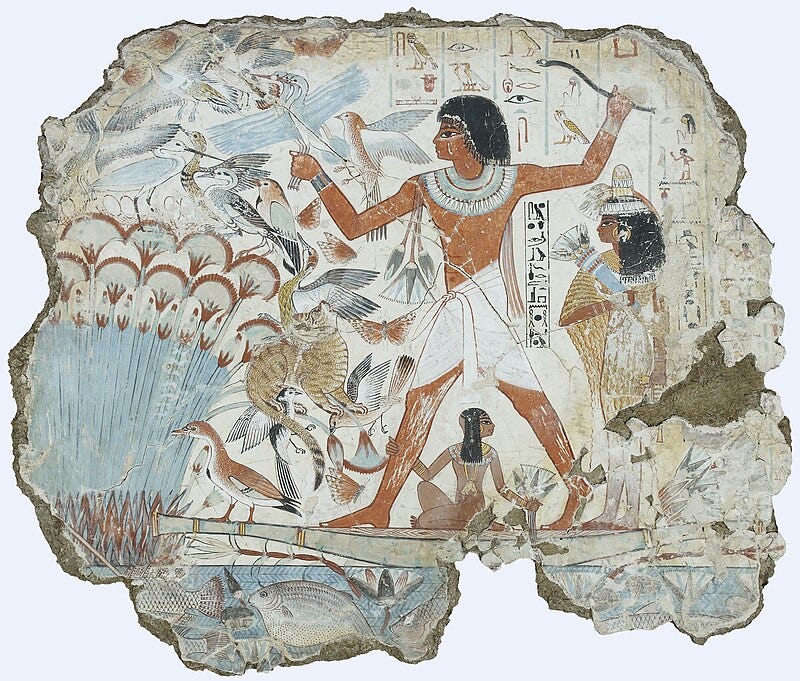

Now look back even further. Around 4500 years ago, Egyptian pharaohs started building pyramids (or rather, having them built). To what extent can we imagine that amount of time- fifty centuries? Even one thousand years seems, in terms of culture and individual lives, an aeon ago. Imagine five such epochs, during which time civilizations rose and fell, languages and beliefs changed beyond recognition, forgotten wars were fought by forgotten heroes whose deeds were lauded for a few centuries before even their memories were finally consigned to the dust. What little we know of the Egyptians comes from the fact that they valued the arts, and were one of the first peoples to write on, paper! What will our civilization bequeath to future ages if we write everything on perishable electronic devices? A single papyrus might outlast its creator by thousands of years, but the contents of a computer chip might vanish forever with the rust and corrosion of a decade. Remember that when all computers are destroyed, even ‘the cloud’ ceases to exist.

Looking further back in time and across the world, New Guinea and Australia have been inhabited by man for at least 40,000 years. Think of your 5 millennia-old pyramids, and then think of the 40 millennia during which people have hunted, fought, farmed, raised families, and told stories in the deep forests of Papua. Many of these tribes were still making stone tools in the 1950s- a tradition preserved unbroken from the Neolithic. Although these cultures had, of course, changed and developed since the stone age, they also preserved many traditions and techniques which were lost in parts of the world where the so-called ‘great civilizations’ plied their influence. A New Guinea Highlander of only a generation ago (sadly these traditions have largely been forgotten today) would have been able to build Stonehenge, using tools similar to those used in Neolithic Britain. Perhaps such people would make the best archaeologists.

The entirety of human existence as we know it unfolds in a period of a few hundred thousand- at the most, one million- years. This is of course, from our everyday perspective, an immense age, but it is nothing compared with the vastness of the Earth’s existence. What seems near-eternal in the mind of a mortal creature is a mere blink of an eye in the great span of time. Scientists often rather glibly speak of these vast ages- ‘it happened 205 million years ago’, as though they had the faintest notion of what that actually means. It isn’t that they are wrong, exactly, but that we would do well to show some humility before a mystery so profound.

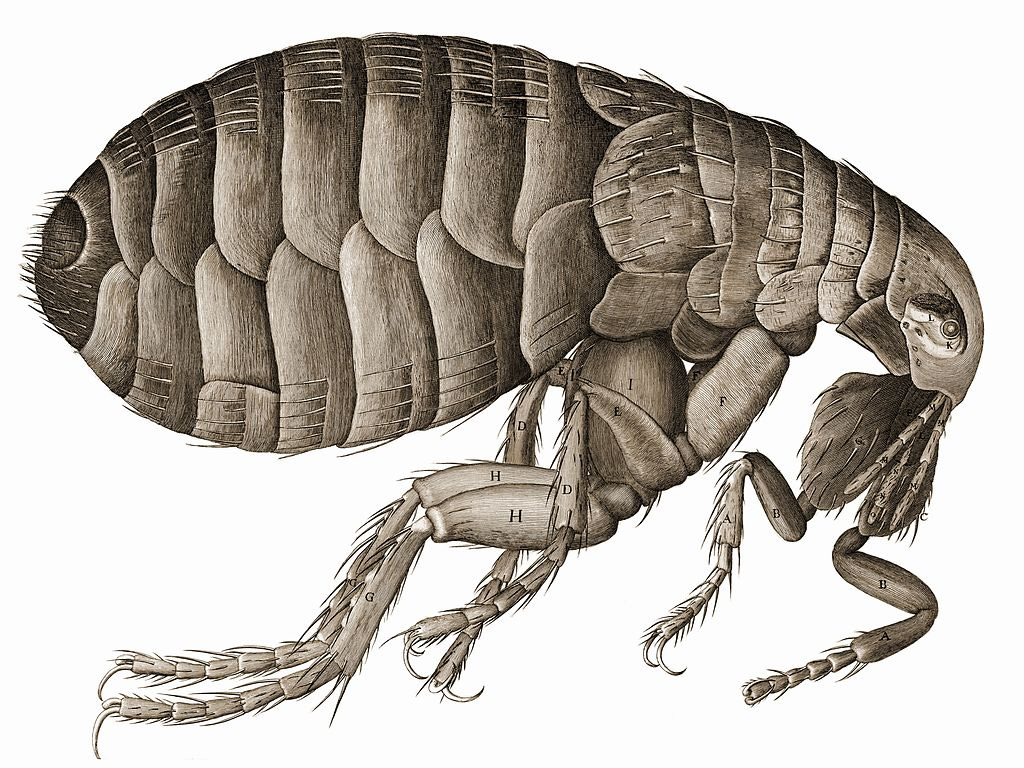

In a similar way, most ‘popular science’ books will at some point mention something of this sort: that a flea can jump over ‘the equivalent of the Eiffel Tower’, or that ants carrying leaves are equivalent to ‘ a man carrying a minivan’, or that a python swallowing a deer is akin to a man ‘eating twice his body weight in hamburgers’. While I appreciate the effort to make nature comprehensible, these things are not really equivalent at all. The world at the scale of an ant’s experience is radically different in nearly every way from our own. An ant could fall off the top of Mount Everest without injury. Small insects are so light that air is more dense relative to their body weight- the smallest of them, in fact, are adapted to ‘swim’ rather than fly through the air, on wings shaped like paddles. The leaves hoisted by leaf-cutter ants have objectively less mass than minivans- the small ant has to exert objectively less force to lift them. These kinds of similes detract from understanding the reality of the flea or ant on its own terms, which is far more interesting.

It should go without saying that truly great scientists and philosophers generally have a more poetic outlook- it is the so-called ‘science communicators’ and ‘public intellectuals’- I need name no names- who are guilty of making trite comparisons into modern-day proverbs, all in the name of education. (Don’t get me started on high school biology textbooks!)

We have similar issues with other dimensions of nature- when we want to make the depth or volume of the ocean understandable, more often than not, comparisons with football fields and the Empire State Building are forthcoming. I have never seen the Empire State Building, which anyway, as far as I know, hasn’t been the tallest structure in the world for quite some time. In my view, Herman Melville described more profoundly the depth of the sea, by putting it poetically, so that his words speak to its meaning in our souls:

“…swallowed him down to living gulfs of doom, and with swift slantings tore him along ‘into the midst of the seas’, where the eddying depths sucked him ten thousand fathoms down and ‘the weeds were wrapped about his head’ and all the watery world of woe bowled over him…. when the whale grounded upon the ocean’s utmost bones….”

-Moby-Dick, IX ‘The Sermon’

Because surely, for all us insignificant people going about our business on the shores of the world, the bottom of the abyss is not simply the sea floor, a measurable distance below our boats and devices, but ‘the ocean’s utmost bones’, beyond the reach of light, beyond all measurement, beyond all understanding except in the deepest depths of the heart.

Which is not to say we should not explore and discover. Such pursuits seem to be burned into the deepest instincts of mankind- ‘to find, to strive, to seek and not to yield’, to quote Tennyson once more. But we should do so with utmost respect before the ungraspable beauty and mystery of the world- the only world- that we are privileged to inhabit.

Is good article. I am reminded that most of my life, or rather, half my life, was spent without computers or cellphone or internet TV. My view of the world is radically different than those whose lives have spanned only the years of those aforementioned electronic devices. My perception of the world and its inhabitants is different. Im glad to have habited a world of mystery and the unknown. Your article highlights those concepts well.

Once again, you are making me, and hopefully all your readers, think. I mean, really think... I woke up this morning feeling bleak and devasted after watching last night's US president's debate. What a mess. Thank you, thank you, thank you, for putting things into perspective. To live our lives as best we can, doing what we must to survive in today's world, but also remembering how small humans are in the vast and unknowable universe...