Ecology is a word often used, less often understood. As the effects of human activity on the environment become more noticeable every year, it has become one of a few scientific terms which have entered popular discussion

Originally, the word was coined by Ernst Haeckel, the late 19th century German biologist and artist, to describe what was commonly referred to as the ‘economy of nature’, a phrase you will find in the writings of early ecological thinkers such as A.R.Wallace. Ecology has the same etymological root as economy, the Greek Oikos, meaning household.

The term, and the associate word ecosystem were used in a strictly academic context for a long time, as the label for that branch of biology which studies how organisms interact in nature, and as the scientific term for such interactions. It wasn’t until the radical ‘60’s when it started to become synonymous with ‘environmentalism’ and ‘save the earth’ activism. Today, I notice that many people are unaware of the original meaning, sometimes even using it as a vaguely defined metaphor for sociological concepts- ‘media ecology’ or ‘the current political ecosystem’.

An Ecologist is not the same as an Environmentalist, and it is quite possible for a person to be either, both or neither of these things. Students of the natural world will of course come to care about its wellbeing, but the two terms are not synonymous. And let’s be clear: there is no ‘media ecology.’ Don’t even get me started on that one.

Fundamentally, ecology is the way in which the parts, so to speak, of natural environments fit together; how, for example, all the plants, birds, and insects in a tropical forest are related. As with systematics (my own scientific background, such as it is), the study of ecology is a science of careful observation, which requires a certain ‘naturalist’s intuition’.

Ecology builds from the ground up, but it grows in leaps and bounds, perhaps exponentially, although without the mathematical precision such a phrase implies. Imagine a patch of sandy soil, perhaps in one of the dryer regions of Western America. At first there is little life- a few beetles scuttling around, lichens growing slowly on a stone. It might not change for years. Then, one rainy season, a seedling takes root: soon a small tree is growing. Sap-sucking insects find the tree- aphids and planthoppers, and ants come collect the sweet honeydew they excrete. Caterpillars and beetles munch the leaves. Other creatures come to eat them- predatory bugs, ladybird beetles, parasitic wasps, spiders. As the leaves fall to earth, they are consumed by fungi, worms and insects, enriching the soil; birds come to hunt insects. Within a few years, there may be hundreds of species gathered around a single tree or shrub. All it takes is one lonely seed to land in a fortunate spot.

I have myself observed a version of this in the sagebrush deserts of eastern Washington- gazing out across an expanse of sand and sagebrush, nestled against a rocky hillside, I once saw a little splash of green, glowing as though dropped by a paintbrush from the heavens, contrasting against the browns and blue-greys of the surrounding landscape. A half-hour’s walk later, and I stood beside a little spring, just a little trickling stream of clear water from some hidden crevice in the basalt cliff. Flying insects dance around it, all manner of herbaceous plants abound beside it, and at my approach a beautifully patterned snake glides out of view. All this abundance of life is due to the chance arrival of wind-borne seeds on the moist ground beside the little spring in the desert.

The relationships between animals, plants and the surrounding environment are not always intuitively obvious. One might assume, for example, that wind-pollinated trees, which do not rely on animals to carry pollen from one to another, have no connection with flower-feeding insects: this turns out to be incorrect- recent studies have shown that willow pollen is an important food resource for bees and flies in early spring before most flowers have opened. This, it turns out, has practical importance for us, because later in the year, those same insects pollinate the crops that provide our food.

Ecosystems which are more structurally complex are more biologically diverse- which is to say, the system keeps building on itself- the more you have, the more you will get. A flower garden attracts more birds and insects than a lawn. This is why simply planting trees- the current trend for corporations and governments looking to ‘offset carbon emissions’- does not guarantee healthy, functioning forests. Forests are not just collections of trees- they are the totality of all their inhabitants, an ecosystem, a collective being. A recently published study of Indonesian tree plantations on Sumatra found, unsurprisingly, a close correlation between forestry practices and the number of native beetle species. Old growth jungle had the most diverse beetle fauna, traditional mixed tree farms (rubber and coffee interspersed with native trees) had a relatively high number of species, while industrial-scale monocultures had a very limited fauna. Healthy old growth forests contain thousands of species of plants and an almost endless number of specialized habitats. A tree plantation contains one kind of plant, and a subsequent lack of habitat diversity. The insects, who are the primary consumers of plant material, are themselves food for reptiles, birds and mammals, many of which are unique endemics found only Indonesian forests.

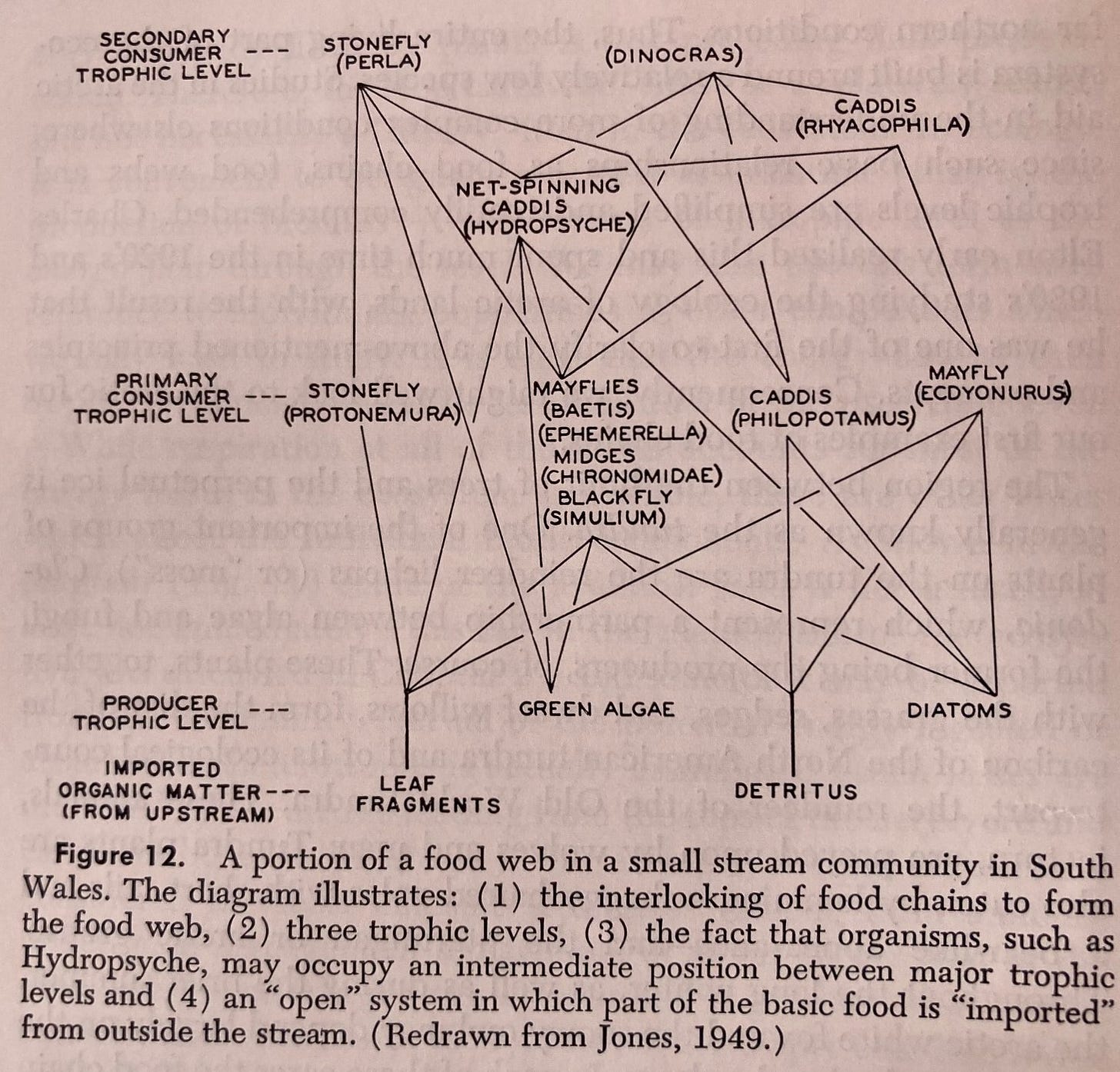

From a biochemical perspective, ecology is based on energy transfer through foraging and hunting- grass turns sunlight into carbohydrates , bison eat the grass and wolves hunt the bison. This is the ‘food chain’, the ecological concept most familiar in popular culture. However, ecosystems are rarely so simple- ecologists prefer to speak of food webs. This shouldn’t be surprising- nature doesn’t work according to flow charts, whatever the diagrams in your ‘BIO 101’ textbook might indicate. An herbivore might be hunted by many predators (lions, wild dogs, hyenas, jackals and crocodiles, for example), which prey on each other as well as competing for hunting territories. A predator’s preference for a particular herbivore might give an advantage to a competing species. Without years of study, we often just don’t know- this can have dire consequences in conservation- we often don’t understand the importance of a particular species until it is gone.

All resources on earth are limited. Every year plants receive a certain amount of energy from the sun, and that energy is the basis of almost all complex life, thanks to that miraculous process of photosynthesis. Without that, life as we know it would not exist- perhaps there would be life on earth, but of a wholly different and unimaginable kind. Plants are the key: ecology calls them ‘primary producers’- a term ripe with meaning for us ‘consumers’ who can’t survive without them.

Ecology is more relevant today than ever before. Large areas of the earth have by now been so altered by development and industry that it would take centuries to restore them to a healthy condition. But the situation is not hopeless. Aside from large-scale efforts to preserve as much ‘unspoiled wilderness’ (a relative term) as possible, everyone who is able can do his or her part by keeping a garden- whether that be acres of pastureland or a few flowerpots on the porch. Every bit helps. Plant things that attract birds and insects. Don’t spray pesticides, and don’t buy bottles of Mason Bees for your plants- native bees are already out there, and in time they will appear, drawn to the flowers by millions of years of instinct.

The various disciplines of natural history are more direly needed today than ever before. So next time you see a kid looking at a bug, don’t scream or discourage: that kid might save us all. It is that sense of wonder at the beauty of nature, inherent in all of us, so easily lost, that is the key to preserving everything in this world that is meaningful.

Beautiful article Cody... I continue to learn new and important things from each article you publish...

A wonderful reminder to be attentive to all the natural wonders around us. Thank you, Cody.